7. One solution, but two new problems

(This article is part of a series. You can jump to the previous section or the next section if you would like to.)

In this section, we will look closer at the limitations floating point numbers have - and how we can mitigate them.

Floating point numbers have varying resolution

The rasterizer now runs on floating point numbers, and uses the rotated vertex coordinates as input for the determinant calculations.

The artifacts we see are gaps between triangles. Does this problem somehow involve the fill rule? Well, yes. Until now we have used an adjustment value of 1, and that has consistently nudged the determinant values so that pixels are not overdrawn, and the triangles have no gaps. The value 1 is the least possible value that will separate pixels exactly on an edge shared between two neighbor triangles - as long as integer coordinates are used.

But now we get gaps. The reason is that we now have higher resolution in all our calculations. The smallest possible difference between two floating point values here is much smaller than 1 – so now we create an unnecessary large separation between neighboring edges.

Actually, the smallest possible difference is not even a constant number. In a floating point representation, the resolution (the shortest distance between two values that can be represented exactly) depends on the value itself. Let’s look at this in detail.

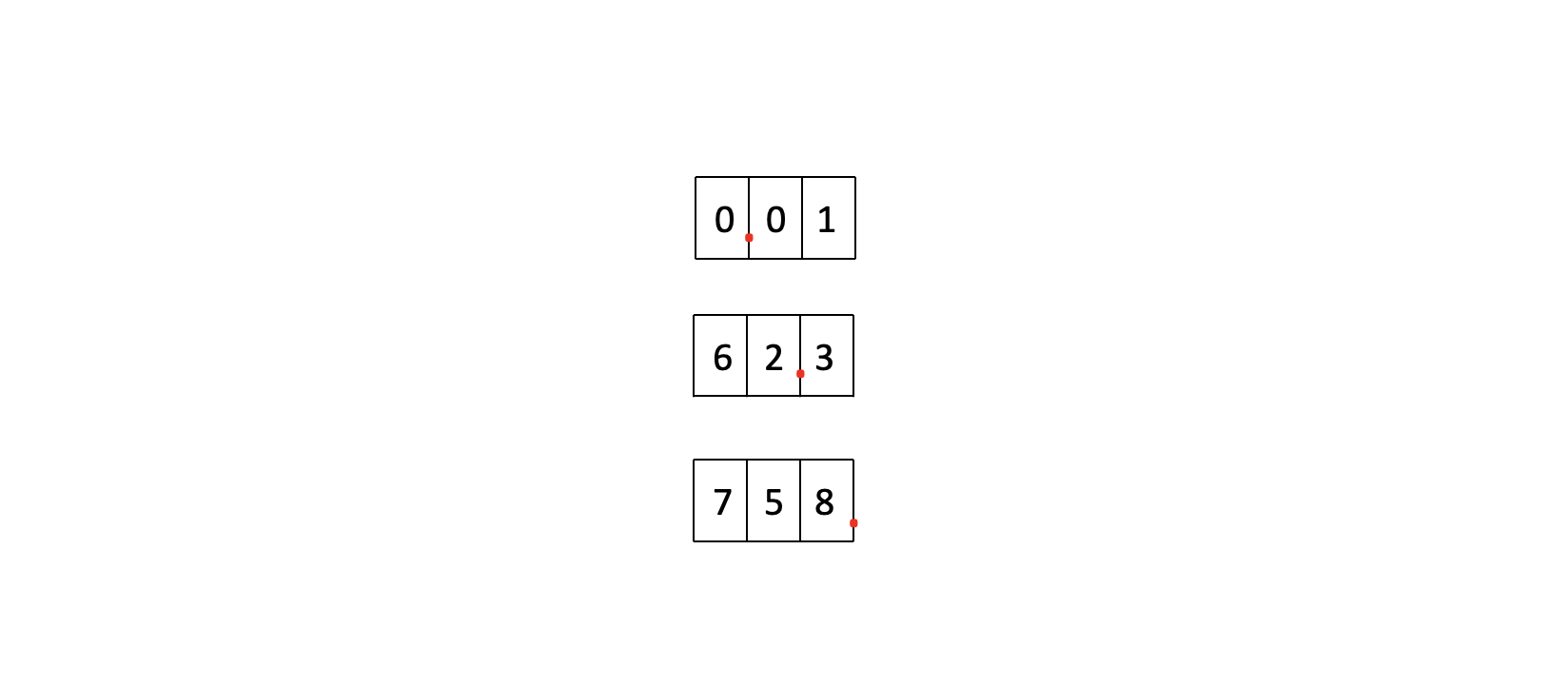

Let’s create a toy floating point format that follows the same structure as the representation normally used in computers. This example format might not be particularly useful in practice, but for now let’s ignore that.

We set aside 3 decimal digits to store the numeric value. As for normal floating point numbers, the total number of digits is fixed, but the decimal can be placed directly after any of the digits. If we ignore negative numbers, the smallest possible value we can represent is 0. The next larger values are 0.01, 0.02, 0.03 and so on. That is, we have a resolution of 0.01. At a value of 9.99 the next larger value becomes 10.0, and after that the next numbers are 10.1, 10.2 and 10.3. So the resolution has become 0.1. After 99.9 comes 100, and then we are at integer resolution - all the way up to the maximum value of 999.

So - the smallest possible value we can use when nudging our determinant will depend on the value of the determinant itself! This is an artifact (or a natural consequence, depending on your expectations) of the floating point representation (the IEEE 754 standard). In numerics, this smallest difference - which we have called resolution here - is often called ULP (Unit of Least Precision).

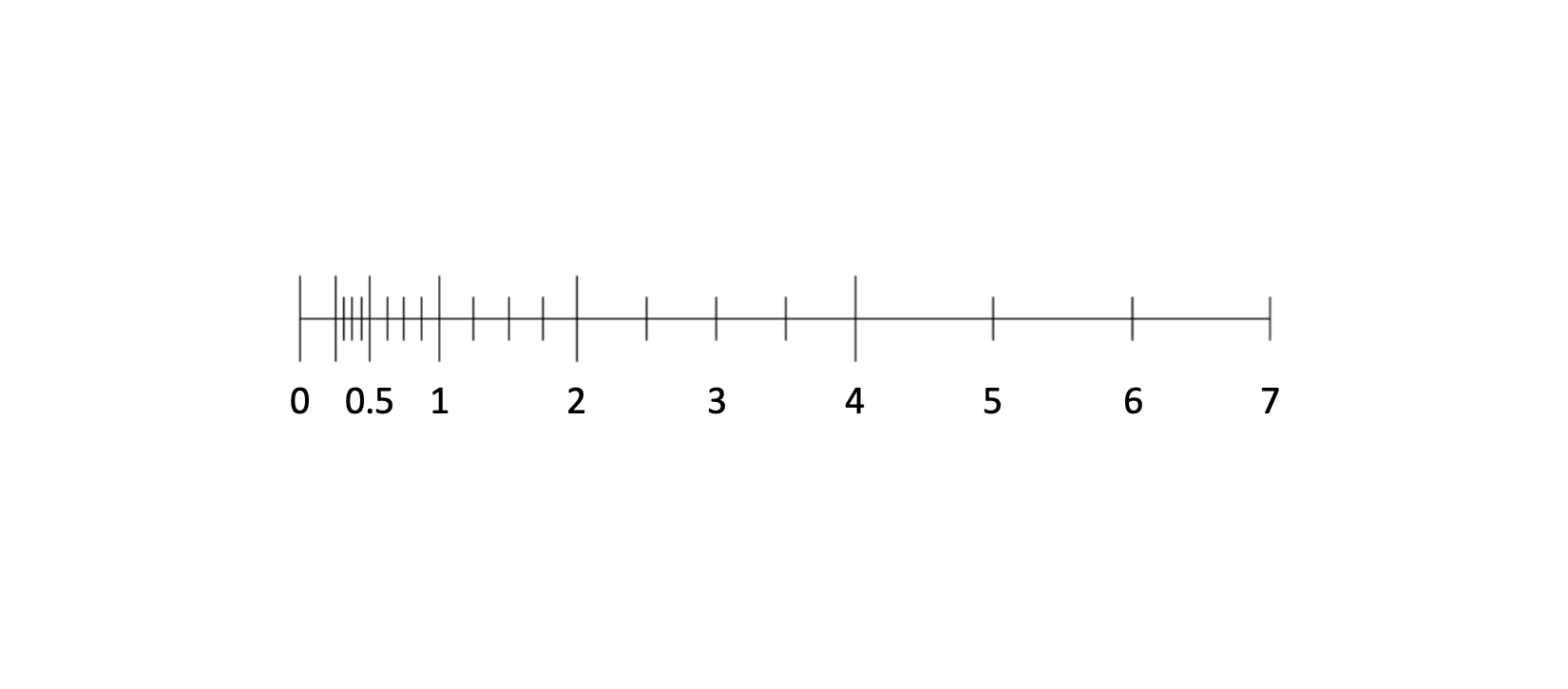

Also, only some of the numbers along the number line can be represented exactly if we use floating point numbers. The other numbers will be nudged to the nearest available representable value. Here is an example of which numbers are representable if you are using a low-precision floating point format. Here, one ULP corresponds to the gap between two short tick marks.

Since the size of an ULP varies, we have varying degrees of exactness in our floating point numbers. As an example, see for yourself what the answer to 0.1 + 0.2 is in JavaScript (which is the language we have used here). Although JavaScript uses double precision (64 bits) when handling numbers, that is still not sufficient. Also, the (perhaps surprising) answer has nothing to do with JavaScript itself - this is due to the way numbers are represented, and is something to be expected for any programming language that implements IEEE 754 correctly.

Calculation issues in floating point numbers

We also hit upon another difficulty: The calculation of the determinant value itself will not necessarily be correct. The resolution we will get will be higher than when using integer values, but the mathematical operations we use to calculate determinants (subtraction and multiplication) are lossy in the floating point domain. Subtractions can incur information loss (due to catastrophic cancellation), and multiplications will scale up errors. This means that the calculated determinant value likely will deviate from what you would get when using pen and paper. It even turns out that determinant calculations are especially tricky to handle (see for example this article).

So, here we have two problems: The determinant values themselves will be imprecise, and at the same time we don’t know how large a suitable adjustment value should be. We need to ensure separation for the tie-breaker rule to work correctly, but here the base results as well as the adjustments on top are uncertain.

The general problem here is that floating point values are not well suited for qualitative use (comparison, logic, rules) when the values are near each other.

The solution: fixed point numbers

Fortunately, we don’t have to solve these problems. Instead, we can use a different representation of our vertex coordinates and determinant values. We can use what is called fixed point numbers. And then, seemingly by magic, our problems disappear!

What is a fixed point number? Let’s have a look.

Like in a floating point representation, we will set a side a given number of digits. But instead of letting the comma be placed anywhere between digits, we will fix it: We place it at the same location for all numbers, hence the name fixed point.

As an example, assume we set a side 4 digits in total, and use 2 digits for the integer part and 2 digits for the fractional part of a number. If we ignore negative numbers we can now represent a numerical range from 0 to 99.99, and the resolution is constant across the entire value range: 0.01. This is convenient. And here comes an extra trick: We can use integers to store these numbers - by storing the original value multiplied by a constant. Assuming we set aside 2 digits for the fractional part, the constant we will then need to multiply by is 100 (10^2). So, the number 47.63 will be represented - and stored - as an integer value of 4673. We can even use normal integer operations to do maths on fixed point numbers. They behave just like integers for addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. When we need to read out the actual value, we divide the fixed point number by the same constant we multiplied by earlier.

Fixed point numbers is the industry standard way to handle the precision problem in triangle rasterization: We use a number representation that provides higher resolution than pure integers, but still gives exact results, and allows us to use fast integer operations for the calculations we need.

But - what happened to the adjustment value? In a fixed point representation there is again such a thing as a smallest possible adjustment value. Our fixed point numbers have a a known resolution (that is constant across the entire value range), and that is exactly the value we want to adjust by. Just as in our old integer-based code. So things are now under control. But now, let us look some more at how we use this number representation.

Implementation details

How do we create fixed point numbers? If we take a floating point number, multiply it by some integer value, and round off the result to an integer, we have made a fixed point representation of the original floating point number.

The multiplication and rounding effectively subdivides the fractional part of the original number into a fixed set of values - ie we quantize the fractional part. This means that we cannot represent all values that a floating point number might have, but we do get the advantage that all mathematical operations on numbers can be realized by their integer variants. So within the available precision we choose for our fixed point numbers, the calculations will be fast and exact. And, as long as we multiply the input by a large enough number, the resolution in the fractional part will be good enough to reach the same animation smoothness as we had when using floating point numbers. At the same time, we keep the correctness and speed we saw in the pure integer implementation. Put differently, we accept bounded and predictable precision loss when converting to fixed point, in exchange for correct - and faster - calculations.

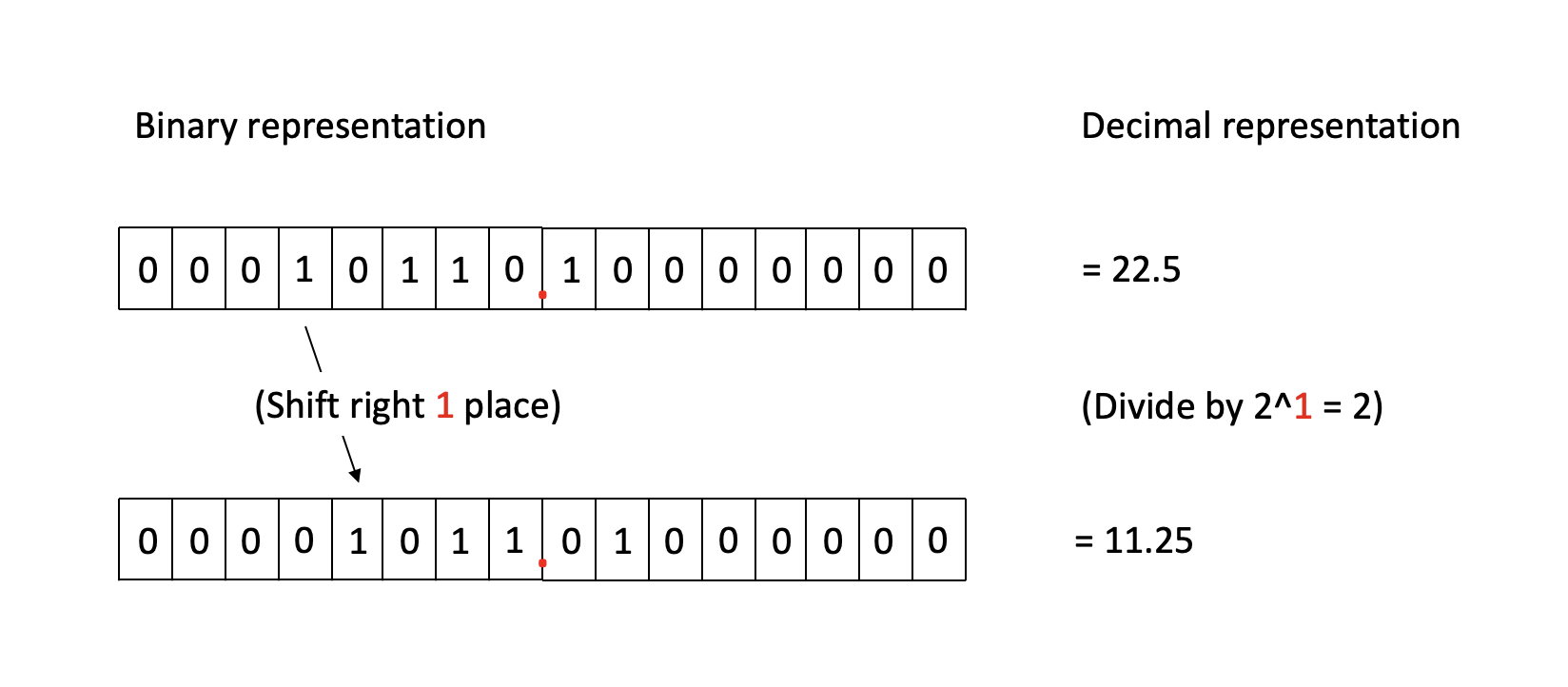

The number we choose to multiply by should be some number 2^n. Then we can convert from a fixed point representation back to a normal number very efficiently. Instead of dividing by 2^n we can bit-shift the number n positions to the right. That is much much faster - but only works for division by 2^n.

This is how bit shifting can replace division:

When we bit-shift n places, we get the same result as division without rounding. This will also remove the fractional part of the number, so it is essentially a trunc or floor operation. If we need to support proper rounding we should add the value 0.5 (converted to fixed point representation) before bit-shifting.

Now, which number 2^n would be right to use? A large number will give us high resolution in the fractional part, but take more space (more bits of storage). And we need to keep both the integer and fractional part within a number of bits that is easily supported by our hardware. Here we choose to use a 32-bit (signed) integer type. We must reserve one bit of storage for the sign (since we need to support negative numbers), so the total amount of bits we can spend on the integer and fractional parts are 31.

If we assume the x and y screen coordinates will be inside the range 0..2048, the integer part would fit inside 11 bits (2^11 = 2048). However, when we calculate the determinant we multiply two fixed point numbers together, and to handle that properly we must set aside double that space. So we need 22 bits for the magnitude - and can spend up to 9 of the remaining bits for the fractional part.

The relations between fixed point numbers, pixels and subpixels

It is here useful to introduce the concept of subpixels. Let’s assume that each whole pixel we see on screen can be divided into smaller, invisible parts - subpixels. The integer part of a fixed point screen coordinate lets us address a whole pixel, and the fractional part lets us address subpixels. So using fixed point coordinates lets us address each subpixel individually and exactly.

This is how a pixel containing 64 subpixels looks like:

![]()

Another way to look at this is to imagine that we create a higher-resolution “invisible grid” of the screen, and perform exact integer calculations on that grid, all while keeping our drawing operations running on the normal pixel grid. In addition, all floating point coordinates undergo the exact same quantization step when they are converted to fixed point numbers. That means they will be snapped to their nearest subpixel location. This is the same type of pixel shifting we saw early on, when we rounded floating point numbers to integers, but now the magnitude of the shifts is much smaller, and it does not visibly affect the smoothness of the animation.

Choosing the right resolution

How smooth does the animation need to be? How many bits should we set aside for the fractional part? If you test some values, you will likely see that you get few noticeable improvements after spending more than 4 bits on the fractional part. So we have chosen that convention here. (The standard for GPUs nowadays seems to be 8 bits of subpixel resolution.)

Choosing 4 bits means we multiply all incoming floating point numbers by 2^4 = 16 before rounding the result off to an integer, and then store that result in an integer variable. To get from a fixed point representation back to a normal number we shift the fixed point number right by 4 places. As mentioned, this conversion essentially is a truncation (a floor operation), so to do proper rounding we will need to add 0.5 (in fixed point representation, meaning, an integer value of 8) to the number before shifting to the right.

In the application code, all of the fixed point operations we need for the rasterizer are implemented in the class FixedPointVector. We will not go through that code here. However, in the next section we will look at how we can convert the rasterizer to use this new and exciting number representation.

There is no code for this section, but I promise: There will be code for the next one.