4. Moar triangles, moar problems

(This article is part of a series. You can jump to the previous section or the next section if you would like to.)

In this section, we will take a closer look at what happens when we draw two triangles that share an edge. There are some important details here that need to be resolved.

Going from one to two triangles

It is not so interesting to look at just one triangle on a screen. We need more triangles! So, let’s add a blue one. In the application code, it looks like this:

const vertices = [];

vertices.push(new Vector(140, 100, 0));

vertices.push(new Vector(140, 40, 0));

vertices.push(new Vector(80, 40, 0));

vertices.push(new Vector(50, 90, 0));

const greenTriangleIndices = [0, 1, 2];

const greenTriangle = new Triangle(greenTriangleIndices, screenBuffer);

const blueTriangleIndices = [0, 2, 3];

const blueTriangle = new Triangle(blueTriangleIndices, screenBuffer);

const greenColor = new Vector(120, 240, 100);

const blueColor = new Vector(100, 180, 240);

We add another vertex to the array of all vertices, and create a new, separate vertex index array just for the blue triangle. Note that the indices 2 and 0 are shared between the two triangles. This means that the two triangles share an edge - that goes between vertices number 2 and 0.

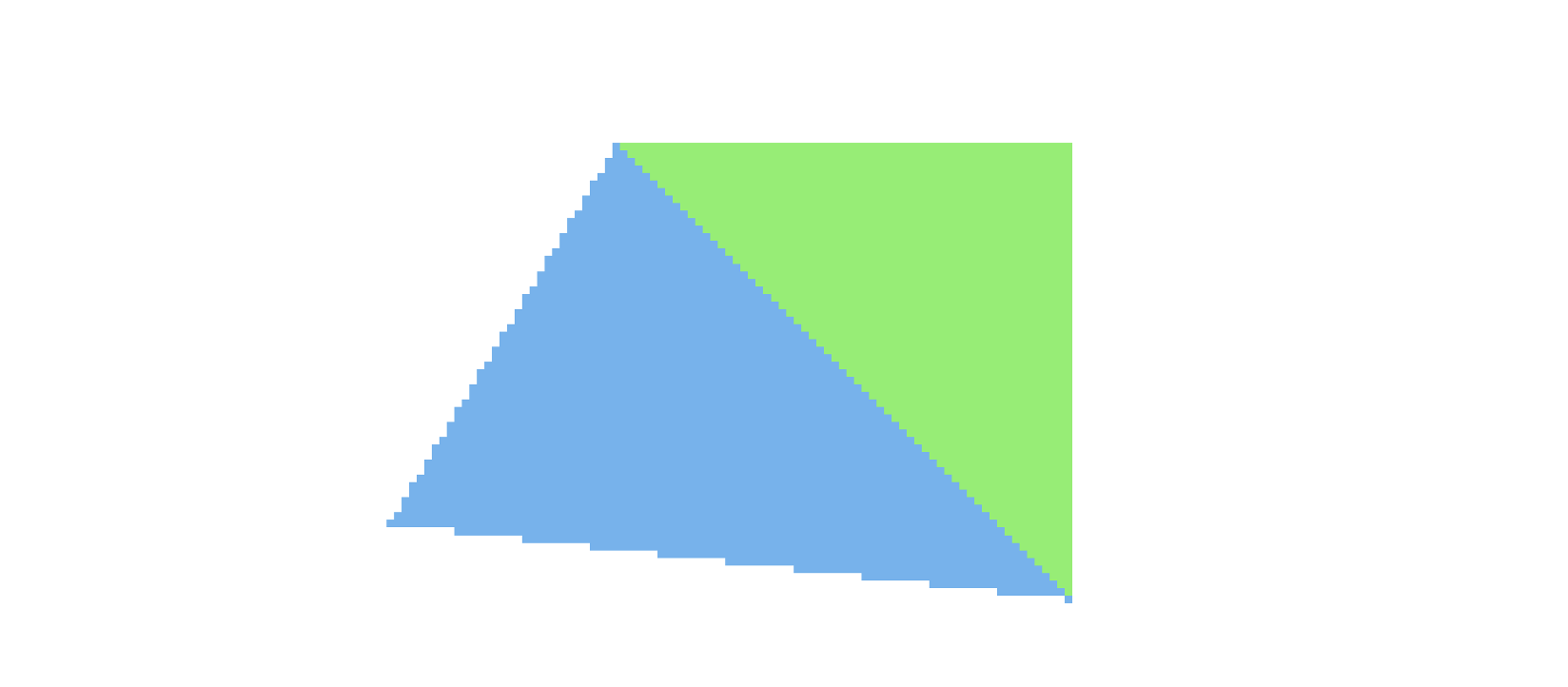

This is how the triangles look like:

Oooops - we have overdraw

At first, this seems to look just great. But, if we draw first the green triangle, and then the blue one, and zoom in on this, we will see that blue pixels on the shared edge are drawn on top of the green ones.

This is called overdraw - and it is something we want to avoid. First of all, it will worsen performance, since we spend time drawing pixels that later become hidden by other pixels. Then, the visual quality will suffer: It will make edges between triangles seem to move, depending on which triangle was drawn first. Should we want to use the rasterizer to draw detailed 3D objects with many triangles, we will in general have no control over the sequence the triangles will be drawn in. The result will look awful - the edges will flicker.

You might remember from earlier that we considered all pixels lying exactly on a triangle edge (w = 0) to belong to the triangle. What we have here is an unfortunate consequence of that: The pixels along the shared edge between two triangles now belong to both triangles. So they are drawn twice.

One rule to rule them all: Fixing overdraw

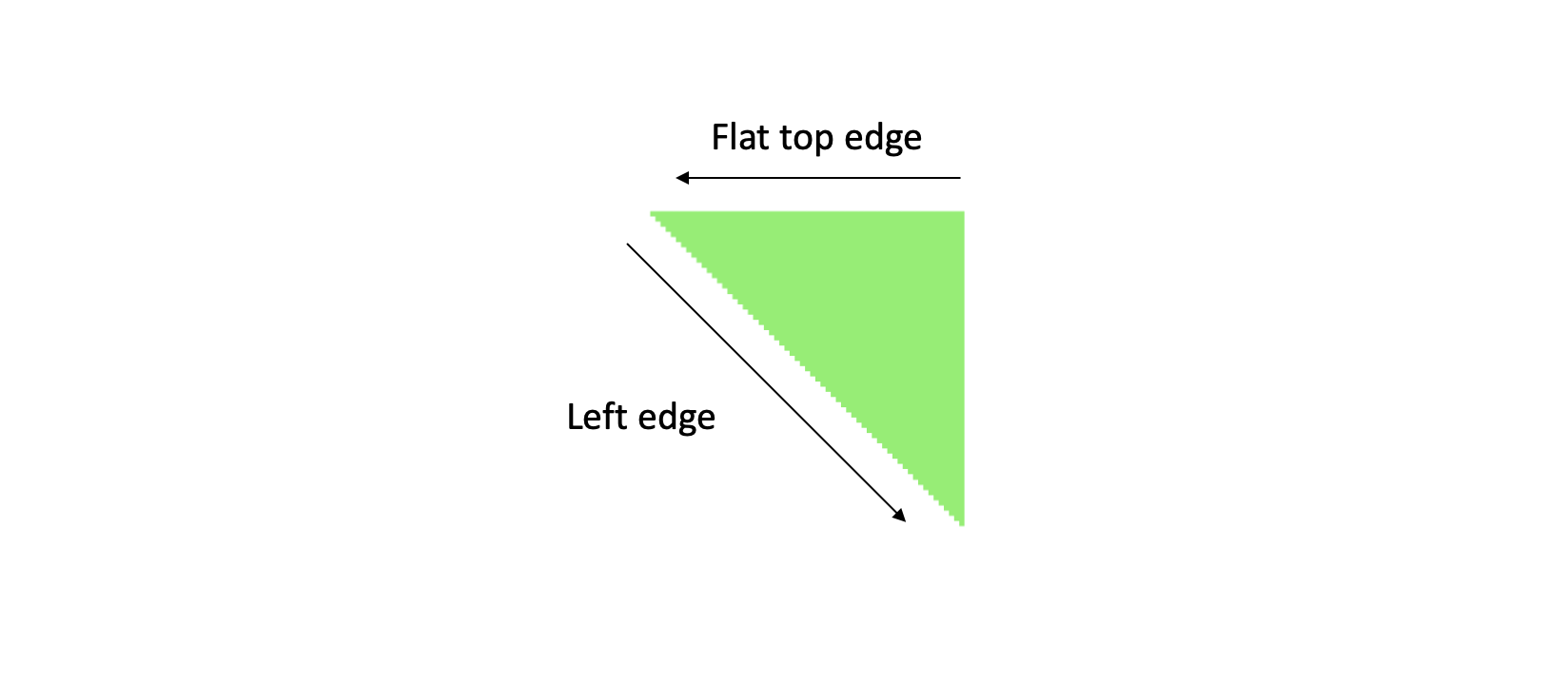

We need to sort out that - and introduce another rule for triangles. The rule that most graphics APIs use, is to say that pixels that lie exactly on a left side edge of a triangle, or on a flat top edge of a triangle, do not belong to that triangle. This is sufficient to cover all cases of shared edges - and make all pixels belong to just one triangle.

The rule is often called the “top left” fill rule, and can be implemented like this, in the triangle rasterizer:

isLeftOrTopEdge(start, end) {

const edge = new Vector(end);

edge.sub(start);

const isLeftEdge = edge[1] > 0;

const isTopEdge = edge[1] == 0 && edge[0] < 0;

return isLeftEdge || isTopEdge;

}

The reasoning behind is as follows: An edge is a left edge if the change in y coordinate, when moving from the end and to the start of the edge, is larger than zero. An edge is a flat top edge if the change in y coordinate is zero and the change in x is negative.

This way of expressing the fill rule is based on two conventions we already follow in our setup: That the vertices in a visible triangle have counterclockwise order, and that the positive y axis on screen points down. As long as those two hold, then the code will work as intended.

(Side note: We could have chosen the opposite convention, and defined a “bottom right” rule, and that would be just as correct. The point is to have a rule that consistently separates pixels that lie on shared edges, and the “top left” version of this rule has somehow become the standard in computer graphics.)

Adjusting edges correctly

Now that we have defined the rule, what do we do with it? How do we express that the pixels on the edges that match the rule do not belong to this triangle?

When drawing pixels, we need to make an exception: We will skip those pixels that - according to this new rule - don’t belong to the triangle after all. An easy way to do so is to adjust the determinant value. So, whenever an edge is affected by the fill rule (ie is a left edge or a horizontal top edge), we subtract some small amount from that determinant.

The goal here is to make the determinant value for pixes on this edge, in the current triangle, differ from the determinant value for pixels on the same edge in the neighbour triangle. The fill rule ensures that we only modify one of the two edges. This way we create a tie breaking rule - ie some logic that ensures that pixels placed exactly on the shared edge will end up belonging to only one of the triangles - and are thus drawn only once.

The adjustment could be considered a dirty trick - since reducing a determinant value essentially moves an edge towards the triangle center. So the change should be as small as possible, while still large enough to give the intended results.

So: How large should the adjustment be? In the setup we have here, all coordinates have integer values. This means that all determinants also have integer values. The resolution - or, smallest expressible value - of the determinant calculation is 1 and that, in turn, means that the smallest possible adjustment value is 1.

if (this.isLeftOrTopEdge(vb, vc)) w[0]--;

if (this.isLeftOrTopEdge(vc, va)) w[1]--;

if (this.isLeftOrTopEdge(va, vb)) w[2]--;

if (w[0] >= 0 && w[1] >= 0 && w[2] >= 0) {

this.buffer.data[imageOffset + 0] = color[0];

this.buffer.data[imageOffset + 1] = color[1];

this.buffer.data[imageOffset + 2] = color[2];

this.buffer.data[imageOffset + 3] = 255;

}

The rest of the code remains the same.

And with that, we can safely draw lots of triangles - without gaps or overlaps! But, we are not done yet. We will now start animating the triangles. See the next section.

If you feel like, you might want to look at the code for this section and the utility classes. There is also a demo app. Press space to show/hide the blue triangle, and f to turn the fill rule on/off.